‘We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope’; Martin Luther King

If he’d ever seen Cuco Martina play in a blue shirt, I bet Dr King’s perspective on hope might be slightly bleaker.

Hope infused Goodison over the summer. For a generation, Blues had longed for another Holy Trinity, but this time one comprised of a good owner, a good manager and money in the bank. After a lengthy wait, it looked as though this long sought after dream might have actually come true.

Following the early summer transfer activity and the belief that more was to come, Evertonians, even those battered by decades of false dawns and shattered dreams, were hopeful that at last, the club was heading somewhere good.

And yet, after an underwhelming start to the campaign hope now seems to be in less ample supply.

As a Blue of thirty-odd years, one who has experienced almost every possible emotion football can throw at a fan, I should be inured to hope. I should recognise supporting Everton for what it is, an exercise where happiness will only ever be fleeting and where hope is best discarded, replaced by cold, brutal realism.

I can’t let it go though. I can’t help looking for mitigation; the ridiculous number of fixtures we’ve had compared to most, the cruelly difficult start to the season, the fact that it’s still early days.

But more than any of this, I’m taking hope from the fact that what is being done at Everton was never going to produce miracles overnight.

When the Blues lined up against Spurs, there were seven players in the starting eleven who weren’t with the club at the end of last season. That is a remarkable (and some would say ridiculous) turnover.

Why would we as fans ever think that changing the side that much and then sending it out to face last year’s runners up was ever going to produce a happy outcome?

Forget talk of missing centre forwards, of the lack of direction, of Martina being unacquainted with even the vaguest concept of defending, what Everton more than anything represent is a club undergoing a herculean transition. And that was never going to be a walk in the park.

When I first began following the club in earnest, something similar was happening at Goodison. It was the early 1980s, a time when footballers still sported tight perms, facial hair was largely restricted to ‘porn’ moustaches and shorts roamed into ‘hot-pants’ territory.

After the Gordon Lee-era came to a close, (a time that had initially promised so much but ended in dire football, drift and relegation fears) in 1981 Everton had turned to a promising young manager in the hope of restoring the club’s fortunes.

Since moving into management with Blackburn Rovers Howard Kendall, a member of Goodison’s original Holy Trinity, had quickly built a reputation as a man to watch. After taking the managerial hot-seat at Ewood Park in 1979, Kendall had pulled the Lancashire club out of the Third Division and into the Second. Having narrowly missed out on promotion to the First during the following campaign, he had caught the eye of a few top-flight clubs.

When he arrived at Goodison he ushered in not just a new approach to the game but also a dizzying amount of transfer activity.

The midfielder, Alan Ainscow arrived from Birmingham City, the mercurial Micky Thomas came from Old Trafford, Mike Walsh was bought from Bolton to shore up the defence, Alan Biley and Mick Ferguson were signed from Derby County and Coventry City respectively to spearhead the attack and two keepers, Blackburn’s Jim Arnold and Bury’s Neville Southall were bought to replace Jim McDonagh between the sticks.

Collectively they were labelled ‘The Magnificent 7’, and as Everton lined up at Goodison to face Birmingham City on the opening day of the season, Kendall’s first in charge, excitement filled the air. That sunny August afternoon was my first at the ground and I can recall a palpable sense of expectation, an atmosphere tingling with possibility.

Two of the new contingent, Ainscow and Biley, scored in that game as Everton eased their way to a 3-1 victory. Goodison crackled. The football was bright. Hope seemed justified.

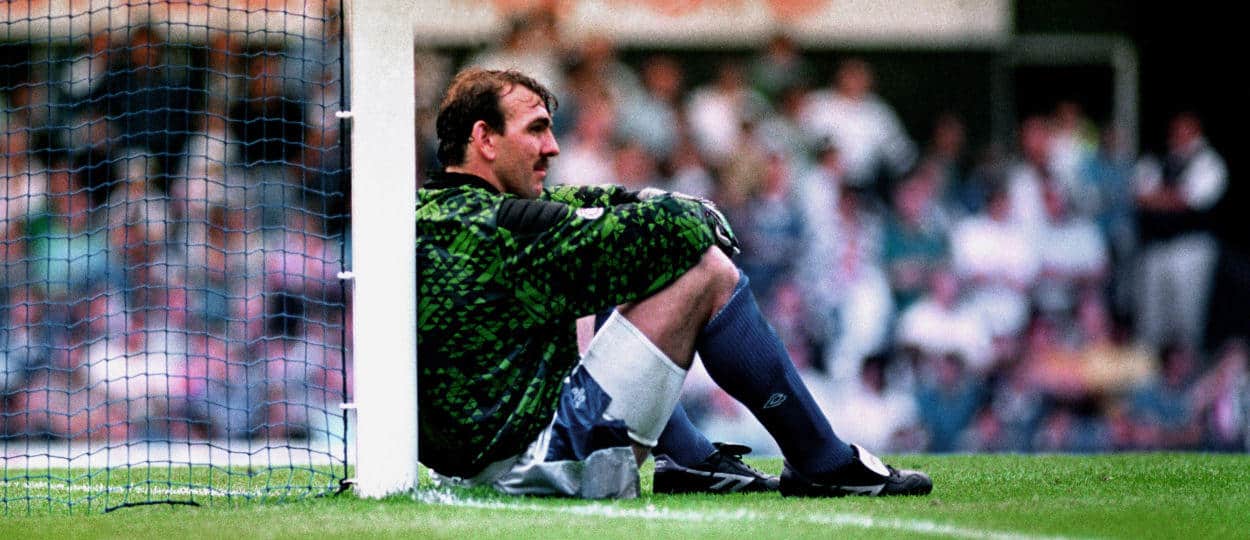

And yet, of those seven that arrived only Southall, who couldn’t even get in the side to begin with, would have a lasting impact at Goodison. As Kendall’s early teams stuttered and stalled, the likes of Ainscow, Ferguson and Walsh would make way for a new generation of Everton players, such as Sharp, Ratcliffe and Stevens, players who would go down in history as amongst the greatest the club has ever seen.

Some of those who became part of Everton’s golden generation, like that triumvirate above, were at the club when Kendall arrived (and other, less heralded signings would come over the following couple of years). The creation of a side that maximised their talents, and those of others, was a lengthy process, one that was often confusing, frequently unsuccessful and not always convincing. But Kendal got there in the end; creating the greatest side to ever grace the Goodison turf.

I’m not suggesting that Koeman is the next Kendall or that the players that we currently have at the club (and might acquire in the future) are collectively going to eclipse what the class of 1985 achieved. But I am suggesting that patience and the willingness to maintain hope should be considered.

Great sides are not built overnight. The wrong players arrive, younger players take time to mature, style and system often take time to emerge.

Everton were in a low place just eighteen months ago, a club heading the wrong way in the league and filled with an array of ‘stellar’ talents who turned out to be not very good at all.

Turning that ship around was always going to take time and was never going to be easy (specifically after losing the squad’s one world class player).

Our transition might come to nothing, that’s always a possibility. Sitting through that first half against Atalanta, it was hard to picture a bright future arriving any time soon. But equally, with a raft of young talent, like Lookman, Calvert-Lewin, Kenny, Holgate and Pickford, teamed with players of maturity, such as Rooney, Sigurdsson , Schneiderlin and Baines we have the blend of youth and experience that bristles with potential.

Not all the players we have today will make it, and several of those that arrived in the summer might turn out to be flops. But hope should remain. The club is in a better position than it has been for a generation and through the long, sometimes frustrating process of transition, a better Everton can still emerge. It has done before. It can do again.

Jim Keoghan is the author of ‘Everton’s Greatest Games’, which is out on 2nd October