Everton v Manchester United 2–1

14 February 1953

FA Cup Fifth Round

Goodison Park. Attendance: 77,920

Everton: O’Neill, Clinton, Lindsay, Jones, Parker, Farrell, Lello, Eglington, Hickson, Buckle, Cummins

Manchester United: Wood, Byrne, Aston, Carey, Lewis, Chilton, Cockburn, Pegg, Berry, Rowley, Pearson

In the early 1950s, Goodison was ruled by a board which seemed determined to hold on to the austerity aesthetic that had so characterised Britain in the late 1940s: the culture of ‘running a tight ship’, of ‘every penny counts’, of ‘make do and mend’. In short, they were tight-arses.

As such, like had not been replaced by like, and instead the club’s prevailing ethos was to put faith in youth (augmented by cheap acquisitions from the lower leagues and Ireland).

The result, inevitably, was disaster. Deteriorating form led eventually, humiliatingly, to relegation. The club ended the 1950/51 season bottom of the First Division, consigning the Blues to their second spell in the second tier.

Down there, life proved tougher than expected, and, for a time, Everton laboured. At one point, early in the second campaign, the Blues were bottom – thoughts of an unprecedented drop to the Third Division North haunting those who followed the club.

Although silver linings were hard to find, a few did exist. The approach of the board might have been largely disastrous, but that isn’t to say that the faith in youth didn’t sometimes bear fruit. Young players such as T. E. Jones, John Willie Parker and Dave Hickson started to make their mark on the first team.

Of these, Hickson was unquestionably the highlight for the fans. Ask any Evertonian who followed the club in the 1950s to name their idol and they will invariably point to the ‘Cannonball Kid’.

‘He was an old-fashioned centre-forward. With his towering blonde quiff, his physical style and a decent eye for goal, Hickson gave us Evertonians something to get excited about in the dark days of the early 1950s. And they were dark. It was a very tough time to be a Blue,’ remembers lifelong Evertonian John Flaherty.

Hickson was tenacious to the point of self-harm, putting his head in places where others might be wary of putting a foot. In was a level of commitment appreciated by the Goodison faithful, who responded to a player that appeared to give his heart and soul for the club every Saturday afternoon.

‘I think Evertonians, as much as they appreciate skills and dexterity, have always taken to their hearts players that give their all for the club. And Hickson was the embodiment of that sort of player,’ continues Flaherty.

It was an approach probably best summed up by Hickson’s own iconic quote, when he said:

‘I would have died for Everton. I would have broken every other bone in my body for any other club I played for but I would have died for this club.’

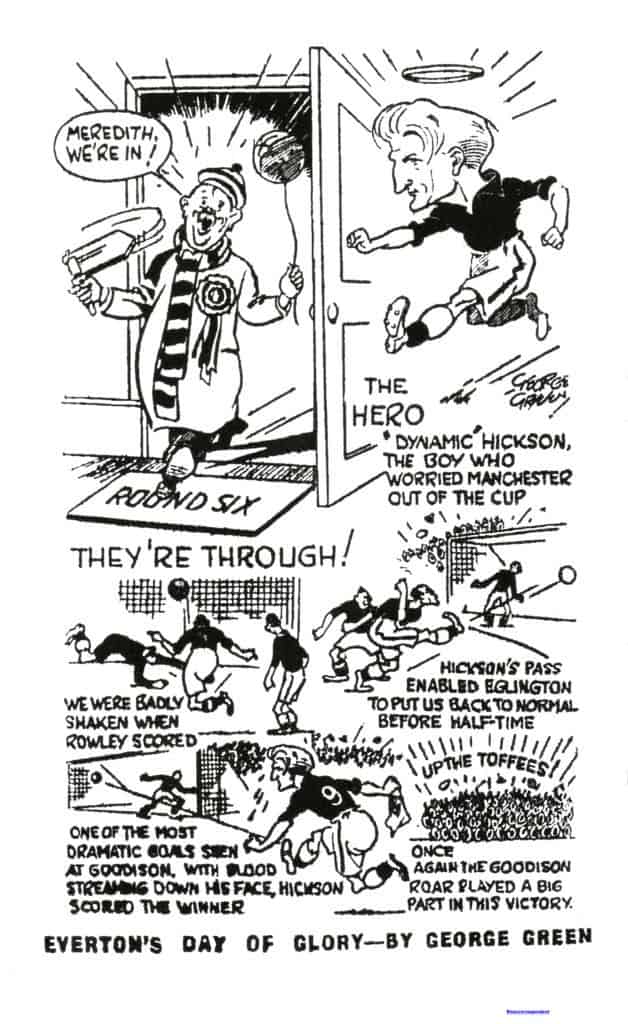

Hickson sealed his reputation for tenacity in a game that also represented another of those bright spots during the bleak 1950s: Everton’s fifth-round FA Cup tie against First Division champions Manchester United.

After some difficult times during the inter-war years, including a few spells in the second tier, Manchester United had emerged as a football force in the immediate post-war era. Under the management of former Liverpool righthalf Matt Busby, United had consistently pushed for the title since top-flight football had resumed in 1946. In 1952, after several near misses, they had eventually clinched it.

On paper, the tie looked relatively straightforward (in so much as an FA Cup game can ever be), the reigning champions playing a side languishing in second tier.

But, despite their threat, United were enduring a tricky season of their own, struggling to recapture their title-winning form. And, as ‘Stork’ reported in the Liverpool Echo, Everton were not to be underestimated:

‘Manchester United will have to sit up and take notice of this Everton team which has not lost a game since January 3. For it has become a competent footballing side with a high degree of confidence in itself.’

In the cup, Everton had dispatched Ipswich Town (3–2) and Nottingham Forest (4–1) in the opening rounds, while United had struggled against Millwall (1–0) and then taken two stabs to dispose of amateur side Walthamstow Avenue (5–2). If form could count for anything, Everton were certainly worth a flutter.

Then again, any punter who had done so would certainly have been cursing that decision if the opening exchanges had been anything to go by.

‘United, while not playing as good football as they used to do 12 months ago, still looked the more dangerous side. When they attacked, it was usually with all forwards up, whereas Everton’s attack frequently saw the inside men well back and the half backs after their defensive efforts unable to lend a hand,’ wrote ‘Ranger’ in the Liverpool Football Echo.

Eventually United’s attacking momentum gave them the advantage, when Rowley put them ahead around the 25-minute mark, seizing on a rebound after the Everton keeper could only parry Berry’s effort away.

The goal, far from disheartening the hosts, seemed to spur Everton into action. Buckle came close on two occasions, and both Chilton and Carey had to make last-ditch interventions to prevent Everton scoring. But the Blues would not be denied for long, and, ten minutes before half-time, they levelled.

‘The start of the movement was a very clever pass by Cummins to Hickson, who was in the outside-right position. Hickson quickly transferred the ball to Eglington who came in to round Aston and then score with a grand right foot shot from ten yards’ distance,’ reported ‘Ranger’.

Five minutes from the break, with the game hammering back and forth, Everton appeared to have been dealt a devastating blow when Hickson dived to connect with a cross, receiving a boot to the head for his troubles. With blood streaming from a cut above his left eye, he was ordered off the field.

Half-time came and went, without Hickson initially remerging after the break. But, unbeknownst to the crowd, the ‘Cannonball Kid’ was being patched up by Harry Cooke, the Everton physio. To the relief of those (home fans) crammed into Goodison, a few seconds after the Everton side had run out on to the field, that recognisable blonde quiff emerged from the tunnel, replete with a hastily stitched-up wound above his right eye.

Shortly after he returned, as Hickson described in his book, The Cannonball Kid, a second collision, this time with the post, almost spelled the end of his game that day:

There was blood and all that everywhere. At this point the referee, Mr Beacock of Scunthorpe, suggested to Peter Farrell [the Everton captain] that I should leave the field.

‘He’ll have to go off,’ said the referee. ‘He can’t go on with an eye like that. He’s not normal.’

There was no way I was going off the pitch, no way at all. ‘I am normal,’ I told him. ‘Tell him I’m normal, Peter, tell him!’ ‘Of course you are Dave,’ said Peter.

‘There you are, Ref,’ I said. ‘I’m staying!’

Blood oozing from his wound, Hickson continued, a decision that paid off not long after, as the man himself later described:

‘On 63 minutes came the game’s decisive moment. I took Tommy Eglington’s pass on my chest, beat one man, sidestepped another and hammered a right-footed shot beyond the reach of Ray Wood and into the net. Goodison erupted in celebration. It was a wonderful moment.’

The remainder of the game was confidently and competently seen out by the home side. ‘Nobody’, wrote ‘Ranger’, ‘seeing Everton for the first time for a couple of months would recognize them as the side they were around about the turn of the year. They fought grimly and resolutely for every ball. They were going to it more quickly than the opposition, and they were swinging it about nicely and their defence covered up even more convincingly than United’s.’

Everton could have extended their lead on several occasions, with Hickson and Parker each having good opportunities. But that extra goal, although sought for, was ultimately not needed. The Blues ended up 2–1 victors, with a huge debt of gratitude owed to their tenacious centre-forward.

‘Hickson was the man of the attack. His grit and determination carried him through despite his handicap and he still chased the ball as though his very life depended on it,’ reported ‘Ranger’, later adding, ‘When the final whistle went O’Neill dashed half the length of the field to throw his arms around Hickson, the hero of a wonderful win.’

Evertonians have always loved their centre-forwards. And, for many, that was the day that Hickson was truly taken into the bosom of the faithful. For as much as the fans respect a forward for his guile, his craft, his skill, they want something more. They want to believe that he feels what the supporters feel, that he loves the club, that he would spill blood for the shirt. Hickson embodied everything that Evertonians want from those who lead the line.

His performance, and those of his team-mates, had earned the Blues a famous win. But there was only so much sunshine to go round that season. Despite the victory, Everton would not make it all the way to Wembley. Although the cup run continued, the Blues faltered in the semis, losing 4–3 to Bolton Wanderers (despite a valiant fightback from 4–0 down).

‘It wasn’t to be. Which was a shame,’ admits John Flaherty. ‘But lucky for us, things were about to get a whole lot better. We were about to see the team get back to where they rightfully belonged.’

This match report is taken from Everton’s Greatest Games: The Toffee’s Fifty Finest Matches,

It is available to buy here: https://www.pitchpublishing.co.uk/shop/everton-greatest-games