Everton v Liverpool 2–0

21 November 1994

Premier League

Goodison Park. Attendance: 39,866

Everton: Southall, Jackson (Rideout), Ablett, Watson, Unsworth, Horne, Parkinson, Ebbrell, Ferguson, Amokachi (Limpar), Hinchcliffe

Liverpool: James, Jones, Scales, Ruddock, Babb, Bjornebye (Redknapp), McManaman, Molby, Barnes, Fowler, Rush

‘I found a squad that was devoid of confidence and which had almost forgotten how to play as a team. I hadn’t really realised just how bad things were. It was a desperate situation at Everton.’

Such was Joe Royle’s damning judgement on the side he had inherited from the outgoing manager Mike Walker. This was November 1994, a dark time for Evertonians.

Mike Walker, a name that will forever haunt fans of the club, had kept his job after the debacle of the previous season, when the Blues had come within millimetres of going down after a death spiral during the second half of the season. Walker, somehow, escaped blame as the club, initially laid culpability for Everton’s dismal form at the door of others.

‘But,’ argues Graham Ennis of When Skies Are Grey, ‘although there were other issues, such as boardroom upheaval and a sense of inertia that had gripped the club, Walker’s role was still integral. He was not right for the job and that was proven as the season started. Everton played as they had in the previous campaign under his management: which was terrible.’

Although benefitting from the financial support of Peter Johnson and bringing in both the players and the playing style he wanted, under Walker the Blues were a disaster. In the 1994/95 season, they took just three points from the first ten games. As Royle took over, Everton sat bottom of the league, a difficult fixture against high-flying Liverpool on the horizon. A change in approach was sorely needed.

‘Everton were too easy to beat, I had to alter that,’ says Royle. ‘Willie Donachie and I watched some videos of the club’s recent performances, and it was obvious that there was a soft underbelly to the side. There was no fight or grit. You need that, especially when you’re fighting relegation. It was our job to bring in a new way of playing and, if needed, the kind of players who could provide that grit.’

When the teams ran out on that cold November night, a shift in personnel illustrated that a change was indeed in the air. The likes of Vinny Samways, Graham Stuart and Gary Rowett, skilful ball players but less likely to hunt down the opposition, were nowhere to be seen. Instead the midfield was staffed by more combative figures, such as Joe Parkinson, Andy Hinchcliffe and Barry Horne.

‘We believed that these players,’ says Royle, ‘when combined to our new approach, which stressed pressing and a quicker tempo, would give us a new dimension. Then, when you add in the crowd, we thought we’d have a fighting chance against Liverpool.’

When this apparently tougher Everton took the pitch, they did so to a rapturous reception. Night games at Goodison always have the capacity to threaten. Chuck in the presence of our ‘esteemed’ neighbours and you have a heady mix. But there was something else there that night: a sense of raw anger too.

‘I think we were all just a bit pissed off,’ says Mike Murphy, who was sitting in the Lower Gwladys Street. ‘It had been a shit year, and everyone was talking up Liverpool. They were flying in the league and we’d obviously been crap, so almost every pundit, and all their fans, just thought it would be a walk in the park. All of that just wound us up. You could feel that anger in the crowd. The atmosphere felt different to pretty much every game I’d been to since Kendall had walked / been pushed a year earlier.’

With the fans conditioned to watching Everton’s anaemic performances under Walker, from kick-off it was evident that Royle had introduced a steelier approach.

‘We worked much harder under Joe,’ recalls Barry Horne, ‘gave teams less chance to play and got the ball upfield quicker. We were a more tenacious side too, one that I doubt few teams would have relished playing. We chased teams, gave them less room to move. But in return, we could still work the ball too. It wasn’t all about the “Dogs of War”. We could play some lovely football.’

Liverpool, who had been dazzling in their attacking play since the season had begun, were suffocated by the Blues. Everton, under their new manager, were a different beast and the likes of McManaman, Molby and Barnes could barely get their feet on the ball, so effective were Royle’s men in closing down space.

But Everton’s new-found fortitude initially came at a cost. The team’s front pairing of Daniel Amokachi and Duncan Ferguson were starved of service from a midfield grouping more defensively minded than most.

Not that much was expected from that duo by the fans. Since arriving from Club Brugge in the summer, Amokachi had disappointed, finding the net just the once. And Ferguson, on loan for three months from Rangers, had been an underwhelming presence, a man who gave no hint of the force he would soon become.

A possible solution to Everton’s attacking impotency presented itself after the break, when an injury to Matt Jackson necessitated a reshuffle. Horne deputised at right-back, Amokachi dropped slightly deeper and Rideout came on to partner Ferguson up front. It was a change that would transform the game and Everton’s season.

‘I was desperate to impress Joe,’ recalls Rideout. ‘What player isn’t when a new manager comes along? To his credit, he’d given us a blank slate, so this was my chance to get out there and show him why I needed to be part of his plans.’

The injection of more attacking potency was dramatic. Amokachi, who always seemed to play better when positioned deeper, started to make driving runs at the Liverpool defence, shattering the composure that they had displayed during the first half.

Allied to this, with two target men to aim at, Hinchcliffe was beginning to whip crosses in with missile-like precision (something that would become a hallmark of Royle’s sides that season).

With the front pairing of Rideout and Ferguson displaying a sense of understanding, this new attacking intent changed the momentum of the game. To add to the steel, which remained marked, Everton now possessed an air of threat. And this was exemplified in the transformation of Ferguson.

After being clattered from behind by Ruddock early in the second half, Everton’s number nine underwent a marked change.

‘Ruddock probably thought he’d done his job,’ remembers Royle. ‘But that nasty challenge brought something out in Duncan. You could almost see him turning green. From the moment he picked himself off the floor he was unplayable.’

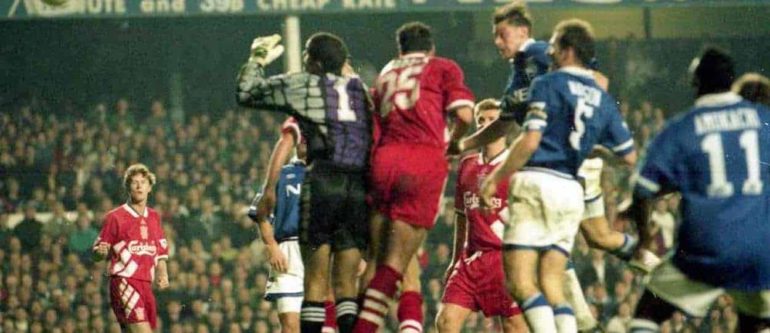

Ferguson’s transformation, combined with Everton’s new attacking potency, meant that the goal, courtesy of the ‘Big Man’, had a sense of inevitability about it.

Stan Osborne, author of Making The Grade, takes up the story: ‘Hinchcliffe’s precision-guided corners had been causing Liverpool problems for a time, but without yielding anything for us. That was about to change. Around the 50-minute mark, Ferguson connected with one and put the ball narrowly over the bar. It was a warning to Liverpool, one that, to their cost, they failed to heed. When Ferguson met the next cross, he didn’t head the ball, he butted it. There was a moment, just as the ball crossed the line but before it hit the back of the net, when Goodison was silent. Then, when we all realised what had happened there was just an explosion of noise.’

Even though the opposition was clearly cowed by the new, invigorated version of Everton, considering Liverpool’s long-held propensity to inflict misery upon the Blues, and the relative distance between the two clubs in the league at the time, it would be natural to assume that a body of supporters as inclined towards the negative as Evertonians would still believe that defeat was inevitable, even after Ferguson had put the side ahead.

‘But that never felt the case that night,’ remembers Tony Murrell, who was sat in the Lower Gwladys Street. ‘It was strange. For once, in a derby, there was a feeling of inevitability about victory. When the second goal came toward the end of the match, it just made perfect sense.’

It was time for Everton’s substitute to show his new manager just what he was capable of. ‘I remember the ball coming in from the left, a high, looping cross from Andy [Hinchcliffe],’ remembers Paul Rideout. ‘Duncan [Ferguson] went up for it against David James, neither of them made a proper connection and the ball fell towards me. I had to reach for it but just about managed to get a poke of a shot at goal. It was strange when the ball went in. I recall the noise of the crowd almost hitting me.’

The reaction of the fans was understandable. As this fixture had loomed in the calendar, it had carried with it a sense of dread. Everton under Walker would have most likely been decimated by this Liverpool side, and the fans were acutely aware of how painful that would have been, specifically as it would have further cemented Everton’s position at the foot of the table.

In securing the win and shackling Liverpool so comprehensively, Everton had not only averted a long-foreseen disaster but also given the supporters hope. Hope that Royle was the right choice. Hope that the Walker nightmare was consigned to the past. Hope that relegation could be avoided.

In a decade largely characterised by disappointment and frustration, that night at Goodison was a rare high point – a night of genuine celebration.

‘One of my favourite memories of that night’, says Graham Ennis, ‘was being on County Road after the match, waiting to get a bus into town and seeing Duncan Ferguson strutting down the road like he was the King of Liverpool. I think that moment sums up how we all felt. We all had the feeling that something had changed.’

It was a feeling that turned out to be accurate. Wins over Chelsea and Leeds followed, and, over the course of the next six months, Royle ushered in a turnaround in form that saw Everton shift from being the worst club in the division to one of the best. And in the process, survival, once thought unimaginable, was achieved.

‘We earned Premier League safety with a game to spare that season,’ says Royle, ‘which, for me, still stands as my greatest managerial achievement. It was a run that had to start somewhere, and it started with that glorious night under the lights, a night when we first showed everyone just what that side could do.’

This Chapter is taken from Everton’s Greatest Games: The Toffee’s Finest Fifty Matches

It is available here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Everton-Greatest-Games-Toffees-Matches/dp/1785313142