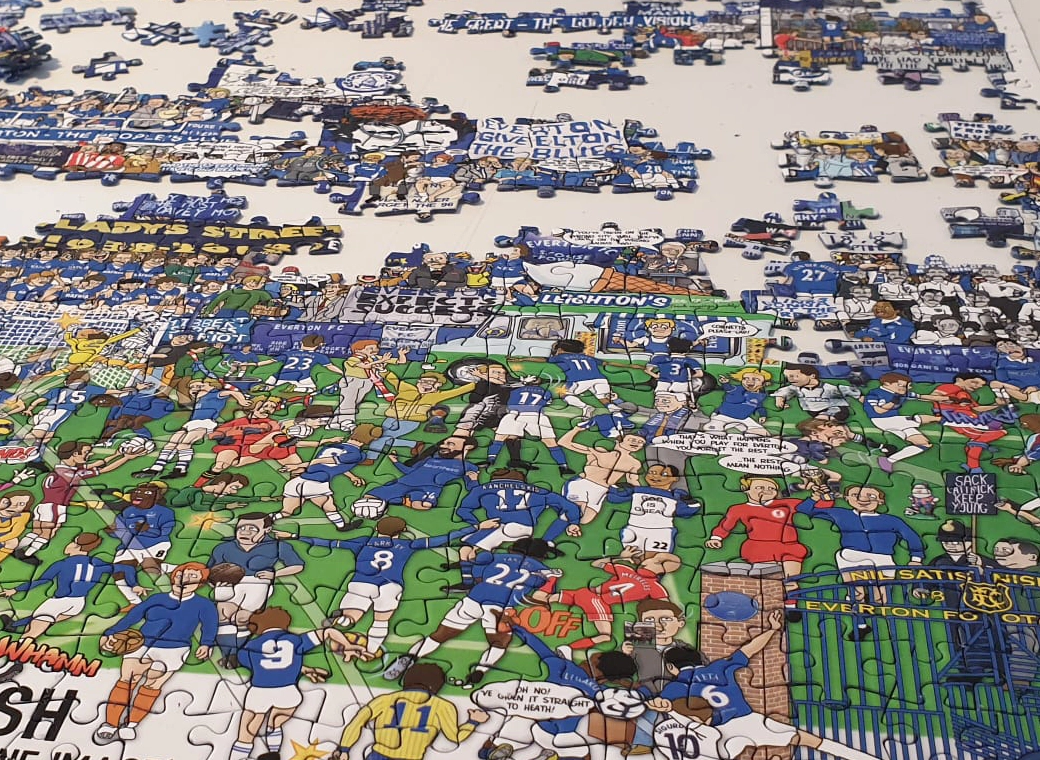

Think these Yanks are capable of building foundations for someone richer than them to come in and do a City.

Heard a while back they're interested in coming in, sorting us a Stadium and improve infrastructure etc and then selling for a profit.

Sounds like what they done with the Padres. Bought for $80 million, built a new stadium whilst redeveloping a run down area and sold for $800 million.

Here's an article on the stadium issue, which sounds very much like the situation we have

http://www.voiceofsandiego.org/topics/land-use/5-lessons-from-the-padres-stadium-push/

Stop me if this sounds familiar.

The owner of one of San Diego’s professional sports franchises said the team’s arrangement with the city wasn’t cutting it. He hinted at a possible move.

Early polls showed most San Diegans weren’t willing to fork over cash for a new ballpark.

That was 16 years and a successful ballot measure ago, and the San Diego Padres now play in one of the

most popular ballparks in the country.

The 1998 win offers a potential playbook for both the Chargers and city leaders looking to craft proposals to keep the NFL team in San Diego.

The 1998 measure was about “more than a ballpark.”

Two decades ago, East Village was an urban wasteland filled with abandoned industrial buildings and dirt lots. It wasn’t a destination, or even a place where many San Diegans lived.

It looked like this.

Photo courtesy of the San Diego Padres

Then-Mayor Susan Golding and an 18-member citizen task force mulling potential ballpark locations seized on the blighted 26-block area east of the Gaslamp Quarter in early 1998.

They recommended that the Padres and the city invest hundreds of millions of dollars into East Village to transform the area into one filled with hotels, new businesses, housing and of course a new ballpark.

So Golding pushed then-Padres owner John Moores to take on a new title: developer.

The final proposal that appeared on the November 1998 ballot called for the Padres to sink at least $115 million into the new ballpark plus other redevelopment projects and ensure hundreds of millions more in private investment, including hundreds of hotel rooms that would help the city recoup its investment.

“They got obligated to build beyond the footprint of the stadium,” said former state lawmaker Steve Peace, who’s now an adviser to Moores. “John Moores is not a developer. He’s a software guy. He’s a geek.”

Yet the Padres capitalized on redevelopment plans during the 1998 campaign – and campaign chief Tom Shepard believes that’s what persuaded voters to support the 1998 ballot measure known as Proposition C.

“It’s more than a ballpark” became the campaign’s slogan. It worked: The message shifted reluctant voters’ attitudes about the proposal, Shepard said.

Here’s what the area looks like today.

.

Photo courtesy of the San Diego Padres

The area is now home to more than 950 hotel rooms, 3,727 housing units and hundreds of thousands of square feet of retail and commercial space,

U-T San Diego reported last year.

Not everyone’s convinced the project has been a complete success.

Ohio State political science professor Vlad Kogan, who co-wrote a

2011 book on San Diego’s government failures, said it’s not clear all the redevelopment and the increased hotel revenues came as a direct result of the new Padres stadium. Kogan said the area was already on the cusp of resurgence because of its location, and it benefited from a Convention Center expansion around the same time, too.

Kogan and coauthor Steve Erie, a retired UC San Diego professor, have long argued that project came with far more fiscal benefit for private companies such as the Moores-affiliated JMI Realty than city coffers or residents.

“Although these redevelopment efforts have generated tremendous private wealth downtown, the millions invested by the city and the (former) Centre City Development Corporation have yielded few public benefits,” they write in “Paradise Plundered: Fiscal Crisis and Governance Failures in San Diego.” “The ‘park at the park’ was the only major new open space constructed in this part of downtown over the past decade.”

The pitch: No money needed from taxpayers.

Then, as now, voters weren’t interested in seeing their tax money flow to a wealthy sports team owner.

The city and the Padres sidestepped those fears by pledging that a redeveloped East Village, complete with revenue-generating hotel rooms, would cover the city’s roughly $300 million investment.

The

ballot measure explained that the city would sell bonds and use hotel and sales tax revenues and tens of millions of new tax dollars allocated by its redevelopment agency to cover those debts. That new cash would also foot the city’s bill for operating the new ballpark.

And Moores promised he’d take the hit if the project went over budget, giving voters further assurances that the day-to-day fund responsible for keeping city operations running would be protected.

The day before the election, the San Diego County Grand Jury dubbed the city’s hotel tax projections too rosy. But that didn’t get much play until after Election Day.

Some of the plans sold to voters have since fallen apart.

The aftermath of Gov. Jerry Brown’s 2011 decision to kill redevelopment

left the city on the hook for the yearly $11.3 million ballpark debt payment

beginning in 2013.

No need for a two-thirds vote.

The Padres and city leaders decided to move forward with a vote anyway to ensure there was enough political will to get the project done.

They ended up nabbing 59.6 percent of the vote on Election Day 1998.

That support helped the ballpark proposal survive a hail of lawsuits, delays and scandals. Among them: City Councilwoman Valerie Stallings’

conviction and forced resignation following revelations that she’d taken unreported gifts from Moores. (The Padres owner managed to avoid charges himself.) And the

infamous Kroll report, which documented the lead-up to San Diego’s pension crisis, suggested city officials delayed the release of a report about the city’s pension issues in 2002 and played down the seriousness of them in a ballpark bond offering out of fear of compromising Petco Park construction.

Padres leadership commanded respect, and won over unlikely supporters.

Moores and then-Padres president Larry Lucchino weren’t strangers to various community groups, key organizations or high-profile local leaders before the 1998 campaign.

The two, especially Lucchino, sat in as two separate citizen task forces analyzed the team’s economic competitiveness, and where the ballpark should go and how the city should pay for it.

That helped the Padres build goodwill.

Then came the campaign, which included cheerleading from Padres players and some unexpected supporters.

Take former City Attorney Mike Aguirre, then a gadfly best known for his work to

force the city to renegotiate its late 1990s deal with the Chargers.

Aguirre accompanied Padres supporters on a trip to Cleveland in fall 1997 to look how the Indians’ new ballpark had helped revitalize the surrounding area.

Aguirre’s experience sold him on the San Diego proposal.

“My judgment was it’s going to be great for downtown,” Aguirre said. “It’s going to stimulate a lot of development down there.”

Shepard recalls Aguirre sketching out campaign plans on a napkin at a Cleveland bar.

“I never thought we’d have Mike Aguirre, to be perfectly honest,” Shepard said.

Aguirre said he later recruited others to join the ballpark cause, too. Among them was Mark Rosentraub, a nationally known sports economics expert critical of publicly subsidized stadiums. Rosentraub eventually became a paid consultant for the ballpark effort and endorsed Prop. C.

Late in the campaign, Shepard said he encouraged Moores and Lucchino to let community leaders like Aguirre make the case for Prop. C.

“The public’s gotta decide it’s good for them and not the team owners,” Shepard said.

Voters didn’t hear as much from ballpark detractors, either. They had less name recognition and less money to spend getting their message out.

The Padres had a blockbuster season.

San Diegans weren’t just hearing the political arguments for a new Padres stadium in fall 1998. They were also cheering on the team in the World Series for just the

second time in their history.

The timing sure didn’t hurt. The games were in mid-October 1998, the final run-up to the election.

That excitement, coupled with testimonies from Padres players and staff, got lots of play on local TV.