The writers at the Economist clearly read GOT

http://www.economist.com/news/europ...rybody-yet-it-still-may-not-happen-ships-pass

LIFE for modern Europeans is marked by endless hardships, not least their inability to buy Hog Island oysters. Farmed in a bay north of San Francisco, these plump, succulent specimens rival anything in Normandy or the Languedoc. Yet there is no transatlantic trade in oysters to speak of. Why? Because of incompatible safety regimes: America tests oyster waters for bacteria while the European Union examines the molluscs themselves. Both methods are sound, but neither side recognises the other’s.

The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), an ambitious planned trade deal between America and the EU, is intended to iron out such wrinkles. Unlike classic free-trade arrangements, TTIP focuses on regulatory and other non-tariff barriers, because levies on most products traded across the Atlantic are already close to zero (exceptions include running shoes and fancy chocolate). Negotiators dream of a world in which pharmaceuticals are subject to the same testing regimes, standards on everything from car design to chemical labelling are harmonised or mutually recognised, and the transatlantic oyster trade is finally liberated. The potential benefits are hard to estimate, but one reasonable guess is that an “ambitious” TTIP could raise America’s GDP by 0.4% and the EU’s by slightly more.

That would be a welcome boost to Europe’s austerity-choked economies and sluggish global trade (see article). It involves neither the political agony of structural reforms nor more public spending. TTIP could also ensure that Europe and America, which account for half of global output, set standards that the rest of the world then has to follow. Officials add that it would cement the transatlantic relationship just as Europeans are getting twitchy about Russia: some speak of an “economic NATO”. This matters especially for east Europeans who have been unnerved by Barack Obama’s strategic “pivot” towards Asia.

And yet TTIP is floundering. Little has been achieved in the 18 months since talks began, and the two sides have sniped at each other for ring-fencing favoured sectors. Delay is not unusual—the EU’s new trade deal with Canada took five years to sew up, a change of the guard has consumed Brussels for months and America has just had mid-term elections. This week Cecilia Malmstrom, the new trade commissioner, was all smiles as she visited Washington, DC, promising a “fresh start”. Trade, she notes, is one of the few areas where the Republican-controlled Congress might offer Mr Obama its co-operation.

The difficulty is that many Europeans would prefer a clean kill to a fresh start. TTIP, cry naysayers, is a Trojan horse that will allow American multinationals to undercut tough European standards that their lobbyists have failed to overturn, or to buy up Britain’s National Health Service. Surprisingly, opposition is strongest in Germany, not previously a bastion of anti-trade activists. For much of the year it has focused on

Chlorhühnchen (chlorine-soaked chicken), an example of the horrors that TTIP’s opponents say would be forced down European throats if doors were opened to American products. Chancellor Angela Merkel insists they should not worry. More recently critics have concentrated on the “investor-state dispute settlement” (ISDS) process, a provision to allow foreign investors to seek arbitration and compensation in the event of expropriation or other governmental misdeeds. Lurking behind all this, say some, is the revival of atavistic anti-Americanism on the German left, spurred in part by revelations that American spies have tapped Mrs Merkel’s phone.

European officials shrug off these teething troubles. TTIP may be the most ambitious trade deal in the EU’s history; little wonder it rubs some up the wrong way. But privately there is frustration at the turn the discussions have taken. The strength of feeling over ISDS has forced the EU temporarily to remove it from the talks while it works out how to proceed. Officials say it is possible to reform the process, perhaps introducing an appeal mechanism and protections against frivolous lawsuits, without killing the deal.

But there is worry on the American side. TTIP is less of a priority for the Obama administration than the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade deal it is pursuing with 11 Asian-Pacific countries. Officials say they are capable of conducting two sets of talks at the same time. But the more Europe drags its feet, the more some will ask if American energies would be better deployed elsewhere. “Quite frankly, we’re puzzled why Europe isn’t gagging for this,” says one American official. A failure to deliver TTIP could also feed adversely into a putative British EU referendum, since those arguing for “Brexit” often claim that Britain on its own would find it easier to strike trade deals with America.

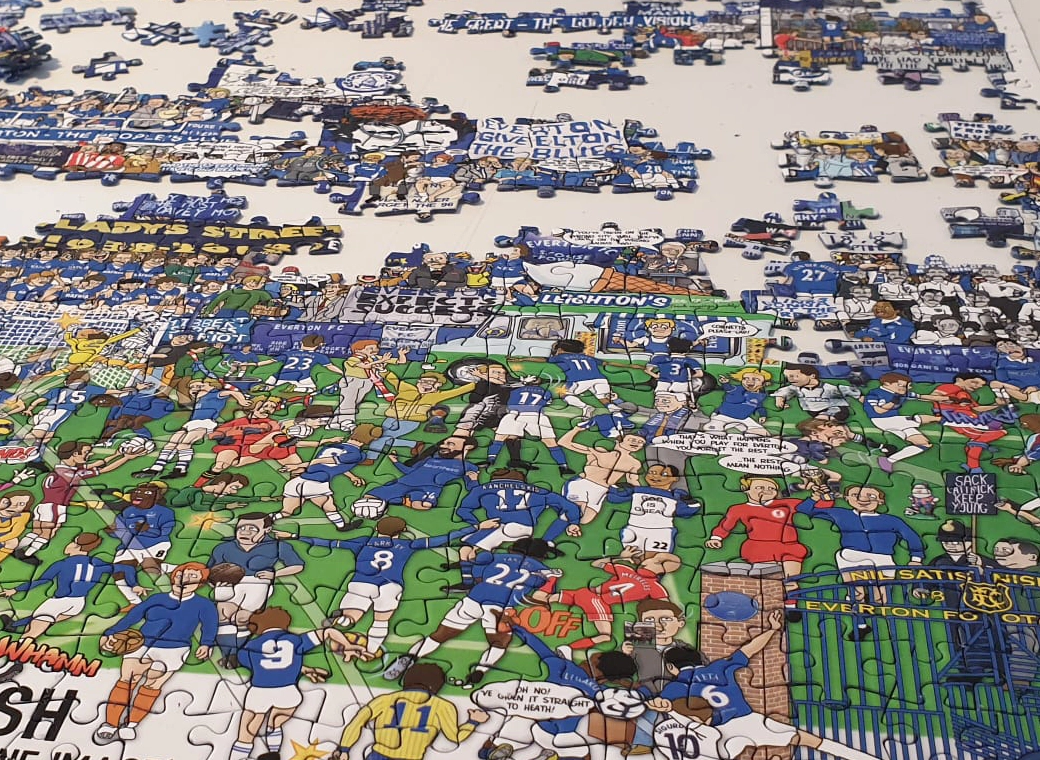

Malmstrom vs the chlorinated chickens

There are signs of a thaw. Last month Sigmar Gabriel, leader of Germany’s Social Democrats and Mrs Merkel’s vice-chancellor, announced his support for the Canadian deal, just two months after saying he could not defend its ISDS provisions. Mrs Merkel herself has become more vocal in her support. American officials say the debate has calmed in recent weeks. They speak warmly of Mrs Malmstrom, and are enthused over Frans Timmermans, a Dutch commissioner seeking to sort out the ISDS issue.

Yet TTIP’s supporters still struggle to make a positive case, forced instead to battle

Chlorhühnchen and other myths. Unlike most previous EU trade deals, TTIP may have to be ratified by national parliaments (as well as the European one), so political critics cannot be ignored. One American cheerleader for the deal says he has learned not to promise Europeans that it will provide jobs and growth; nobody believes this. More effective is a piece of flattery: that TTIP is essentially an extension of the EU’s single market to a friendly partner. Supporters might try mentioning oysters, too, for TTIP needs all the help it can get.